A decade later, the parasite MSX ( Haplosporidium nelsoni) infected oysters where salinity was at least 15 parts per thousand (15ppt).īoth diseases killed oysters before they reached marketable size, but oyster beds in the Rappahannock River survived better. The single-celled protozoan parasite known as Dermo ( Perkinsus marinus) was first identified in the Chesapeake Bay in 1949. The political and economic reasons for authorizing harvest of restored sites was joined by a biological reason, starting in the 1950's. Few people considered re-establishing oyster bars without harvesting the oysters, just to provide filter-feeders that could help to re-balance the ecology of the Chesapeake Bay. The put-and-take restoration approach was not a cost-effective was to increase the oyster population, but it was politically popular in the thinly-populated counties along the Chesapeake Bay.īecause the new oysters were quickly harvested, restoration efforts failed to increase the overall population of oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. The oyster restoration process was a subsidy for a traditional industry. The public paid for increasing the oyster supply, though only few private individuals quickly harvested the benefits. The state investment in oyster restoration on public rocks was justified in part because it created economic opportunities for the watermen and the influential oyster shucking houses. Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery: Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan - Maryland and Virginia Oyster shell with spat, suitable for transplanting as a seed oyster Restoration on public rocks became a put-and-take fishery, comparable to annual stocking of trout in mountain streams for recreational fishing. That limited natural oyster reproduction. Tonguing and dredging dispersed the shells on the public rocks, reducing three-dimensional reefs into scattered piles.

More oysters grew, but the state did not impose tight restrictions on harvest. Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Norfolk: Public Oyster Grounds (1892)Įxpanding the square footage of hard substrate created more suitable oyster habitat on the river bottom. The Baylor Surveys defined the boundaries of public oyster grounds in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River The "public rocks" were available for public harvest by watermen who could not afford to pay for private leases and develop "private rocks." Oyster shells were dumped on the natural oyster bars, not the barren submerged lands identified in the Baylor Surveys and then leased for private aquaculture initiatives. The state used public funding to restore natural, still-producing oyster bars within the areas delineated in the Baylor Surveys. The Ballard Fish & Oyster Company on the Eastern Shore still advertises that is has been " producing great shellfish since 1895." 1 The shells were shipped to privately-leased submerged tracts, then stocked with young seed oysters that were often harvested from the living reefs on the James River.Īfter a year or two, the seed oysters grew to market size and were harvested by the leaseholder - assuming an unauthorized oyster pirate had not scraped up those oysters illegally. Leaseholders bought old oyster shells from packing houses or dredged them from fossil oyster reefs in the James River. However, the right to harvest the oysters that grew on "private rocks" (submerged land leased by the Commonwealth of Virginia) was limited to the leaseholder. Private aquaculture used the same techniques as the state used on public oyster grounds. Yates between 1906-1912.) In Virginia, these barren areas were made available for lease (privatized) at very low cost per acre. (Maryland defined its Natural Oyster Bars in surveys by C.C. In 1892-94, the Baylor Surveys in Virginia delineated areas where oysters were growing naturally and identified submerged lands that were barren of oysters. Oyster restoration began on a large scale in Virginia at the start of the 20th Century, by private individuals who had an economic interest in growing oysters for profit.

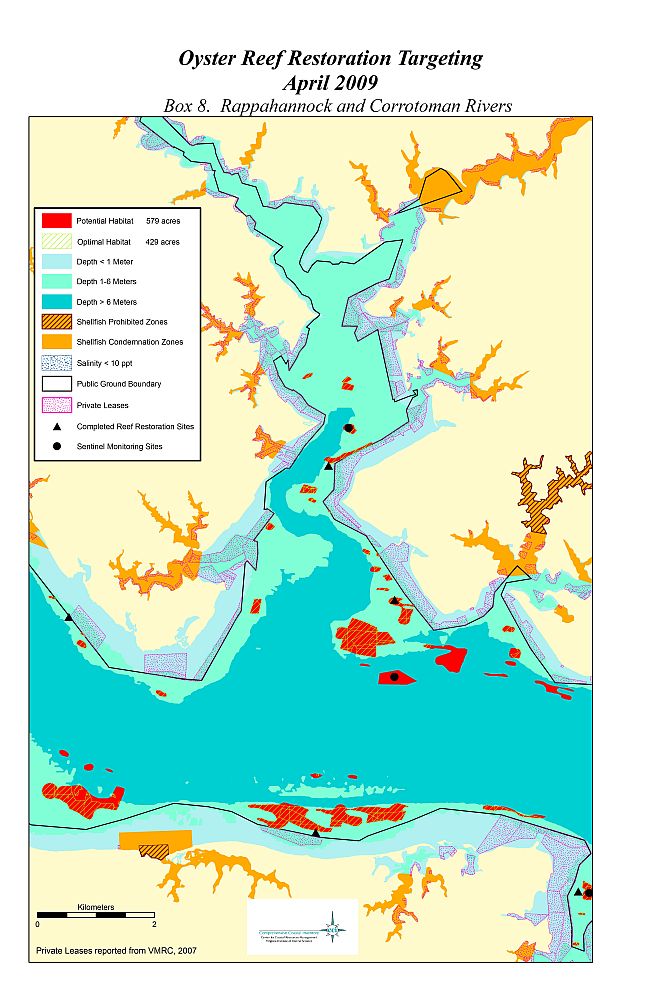

Source: Virginia Oyster Reef Restoration Map Atlas Oyster restoration site, confluence of Nansemond and James rivers

Oyster Restoration in Virginia Oyster Restoration in Virginia

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)